Placemaking is the Welsh Government’s way of realising the Wellbeing of Future Generation goals through the planning system. At the “Eisteddfod Amgen” (the virtual Eisteddfod) in August Owain Wyn, BURUM and Dr Kathryn Jones, Cwmni Iaith presented a webinar looking at land use planning in Wales from the perspective of “a Wales ...with a thriving Welsh language”, and in particular, the Government’s target of realising a million Welsh speakers by 2050. This article by Owain summarises that presentation and discusses from an interdisciplinary perspective what planners can and should do to strengthen Placemaking's contribution to the national effort.

The legislative context for this paper is twofold. Firstly, the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act places a duty on public bodies to promote sustainable development and, as one of its seven goals, “a Wales of vibrant culture and thriving Welsh language”. Secondly, whilst the Planning (Wales) Act does not cover the issue of ensuring a thriving Welsh language directly it addresses development planning and the Welsh language in terms of avoiding harm. “The appraisal(s).... must include an assessment of the likely effects of the policies in the draft Framework/plan on the use of the Welsh language.” [1]

The policy and strategic context has developed considerably since these 2015 Acts. Cymraeg 2050 [2] was published in June 2017 and is the Welsh Government's headline ambition of realising a million Welsh speakers by 2050. This is from a position of around 560,000 recorded at the 2011 Census – an increase of 440,000. The policy framework has two other themes. Its second theme is to increase the use of Welsh by seeking to double the number of speakers who use Welsh daily from 10% in 2013 to 20% by 2050 – again an increase of around 300,000. The third theme is to create the appropriate economic and social context and conditions favourable for this growth, and directly relates to the role of Placemaking.

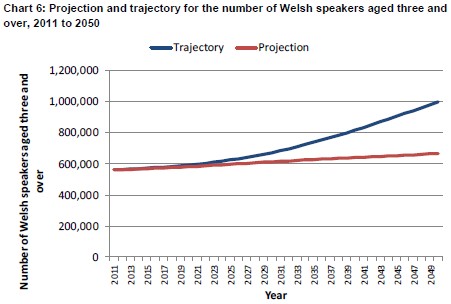

Welsh Government’s focus for the growth in numbers is primarily on producing speakers through the primary and secondary education system, and then on retaining bilingual ability post education. The trajectory envisages an increase in the number of speakers by around 230,000 by 2043 (over 2011).

The population for Wales age 3 and over is projected by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to be around 3.2 million by 2043[3], an increase of 5.4% over the 2018 baseline. As a proportion of the projected population therefore the trajectory envisages an increase in the number of Welsh speakers, in percentage terms, from around 19 % in 2011 to a little under 26% - or approximately 1 in 4 - by 2043.

Figure 1: Cymraeg 2050: Trajectory and Projection

Source: Welsh Government Statistics for Wales (2018) Technical report: Projection and Trajectory for the number of Welsh speakers aged three and over, 2011 to 2050

This next period is within the timescale of the National Development Framework, probably those of the proposed Strategic Development Plans (SDPs) and increasingly those of Local Development Plans (LDPs) as they are reviewed and the second round of Local Development Plans (LDP2s) are produced.

Yet, so far, there is very little evidence that Welsh Government – through Cymraeg 2050 and Placemaking - is addressing where the increase of 200,000 + is to take place and whether it has considered - in sufficient depth and clarity - what favourable economic and social context and conditions are needed to accommodate this growth.

Despite being published after Cymraeg 2050, TAN 20 (2017) and Planning Policy for Wales edition 10 (2018) - whilst encouraging support for the language - have little specific detail on how Placemaking could and should play a part in enabling the Welsh language to thrive as a community language.

Future Wales - the Draft National Development Framework [4] - has as one of its 11 outcomes “A Wales where people live …. In places with a thriving Welsh language”. Encouragingly, it also now proposes that “the language will be an embedded consideration in the spatial strategy of all development plans”. The supporting text for each of the four regions also contains a baseline figure of Welsh speakers and guidance to the effect that “Strategic and Local Development Plans consider the relationship strategic housing, transport and economic growth and the Welsh language “and S/LPDs “should contain settlement hierarchies and growth distribution policies that create condition for Welsh to thrive and remain as the community language (language of every day use in the South East)”. Nevertheless it does not have a specific Strategic Spatial Policy that might identify and support where development might be encouraged to support areas where Welsh is the everyday language or to enable the language to develop as a natural , thriving part of communities and thus to support the outcome.

I appreciate of course that Placemaking cannot look at the Welsh language in isolation. But surely delivering high quality sustainable places with a thriving Welsh language involves better integration of policy areas and better collaboration between linguistic and spatial planners? Having a common and integrated problem-solving outlook will help address certain key “wicked issues”.

One of, if not the main problem, at the heart of this matter is better understanding of the relationship between a cultural and social phenomenon such as language and the development and use of land. We all say positive things about creating the right conditions for the Welsh language to thrive but how can Placemaking maximise the conditions that will encourage an increase in the number and percentage of Welsh speakers across Wales and an increase in the number of people who speak Welsh daily? In other words what can Planning do?

Historically, “development” is perceived as having had an adverse impact on the language in Wales. However, the actual numbers of Welsh speakers continued to grow until the 1911 Census coinciding with the growth of extractive industries and industrialisation in Wales. Without oversimplifying, it is the consequences of wars, the interwar depression, migration, the lack of relative status in public administration, economic and education life (until the nineties), the lack of transmission from one generation to another and the impact of comparatively large net in-migration over the last fifty years (beyond the capacity of local communities to absorb such increase) that, in combination, have largely resulted in the decline in the numbers and proportion of Welsh speakers.

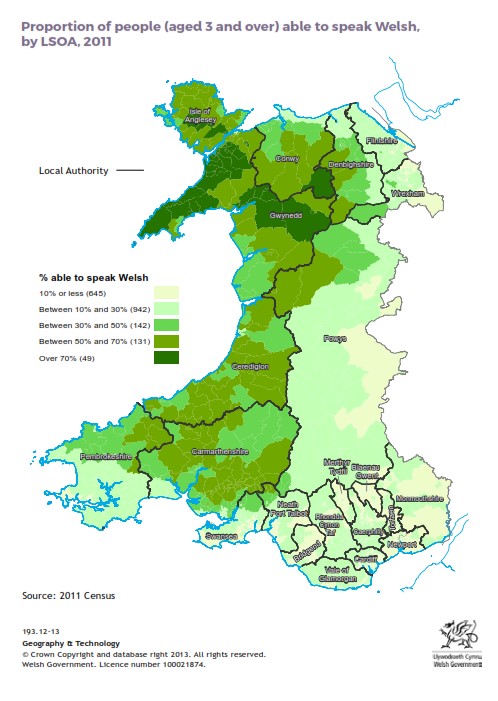

Figure 2 The Baseline Distribution. Proportion of people aged 3 and over able to speak Welsh 2011 by band of intensity

Source: Welsh Government (reproduced in Cymraeg 2050)

Sustainable development, in theory should mean a scale and location of development that does not go beyond the capacity of communities to absorb such development. This will also allow linguistic production and reproduction to increase the number and proportion of speakers - and the opportunity to use other tools in combination to create the right conditions for daily usage.

Secondly, in order to help Placemaking, both spatial and language planners need to identify a clearer spatial element to their ambitions. Cymraeg 2050 does not address the issue of where growth is to take place. TAN 20 talks about areas of linguistic sensitivity but also, crucially, about areas of linguistic importance. However, it does not adopt a prescriptive approach but rather lays the onus on local planning authorities to identify such areas. One assumes that LPAs are thus to view sensitivity or importance with reference to the local rather national context.

Most, if not all, recognise that for a language to survive as a social phenomenon beyond the home it needs a heartland. But if most of the increase of 230,000 (and proportions and usage) is to come from the more urbanised north east and south east what implications does this have for development planning and decision making? Within the context of a relatively static national population by the mid-thirties decisions about preferred scale and location of development will have critical importance for language planning.

Working across Wales will mean different approaches. However, rather than taking their benchmark as the present or recent past, LPAs need to understand the difference the various scale and location options the LP upon the Welsh language can take in terms of the future trajectory (the “business as usual” assumption about Cymraeg 2050). Indeed, why should LPAs not consider a “Welsh language-led growth” option (alongside such options as employment growth led, household growth led, nature resilience-led) as one of its reasonable alternative options in carrying out its Integrated Sustainability Appraisal?

An analysis of Welsh Government’s recent responses (Regulation 15) and/or objections (Regulation 17) to the first wave of LDP reviews, whether at Preferred Strategy, Pre-Deposit or Deposit Stage appears to support this view. The Plans Branch responses appear to have common themes:

- The LPAs in question need to better demonstrate how the need to protect and enhance the Welsh Language has influenced their choice of preferred scale and spatial distribution of growth.

- Lack of evidence, clarity or certainty as to whether, or how, the LPA in question has considered the need to identify areas of linguistic sensitivity, (note – not importance).

- Need for more LPAs to have a Welsh language policy to cover major unanticipated proposals.

In addition, up to now it appears that impact on the Welsh Language on preferred scales and spatial distribution of growth is only raised with certain LPAs and not others. It is unclear what criteria the Plans Branch has used to decided which LPAs are “sensitive” and/or “important” from a Placemaking perspective. This aspect should become clearer from now on as a result of the changes to the Future Wales document referred to above where it is proposed that all development plans will need to consider the language in their choice of spatial strategy.

Thirdly, in relation to the contribution of Placemaking, is the need to accelerate our monitoring and evaluation efforts to understand the impact of plans on the Welsh language. Despite the Welsh language being recognised as a potential consideration in plan and decision making for the best part of thirty years, monitoring and evaluation of the impact of the planning system on the Welsh language remains piecemeal at best. If Placemaking is to be judged on its added value in creating a thriving Welsh language then proper structures and resourcing need to be put in place - at national, strategic and local levels – to measure and evaluate that contribution.

Fourthly, Placemaking needs to make much more and better use of its tools to maximise enhancements - in addition to mitigating risks - as it does in other fields such as biodiversity. For example, major allocations – particularly in areas of linguistic sensitivity and/or importance, need to enhance benefits. For example, these could be in the form of financial or tangible contributions toward the creation of a Welsh medium school, supporting Welsh speaking networks, the employment of an animateur or monitoring and evaluation structure(s). Similarly, developers of major unanticipated proposals should be encouraged for the outset to plan in terms of enhancement - in addition to including mitigation actions - to seek to make their developments acceptable.

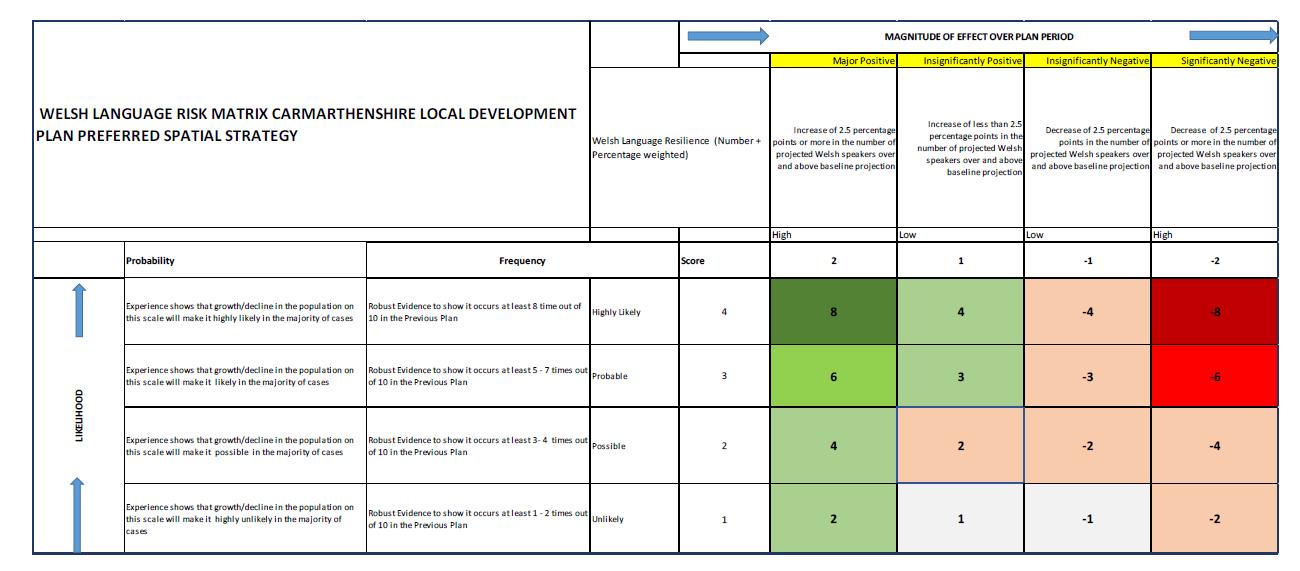

Finally, the fifth point is the need to establish how the quality of Welsh Language Impact Assessments (WLIAs) should be improved and judged and by whom. In our presentation we described the limitations of the current mainstream methodology “Planning and the Welsh Language – the Way Forward”[5] and our emerging work in developing an approach based on the ISO-31000(2009) Risk Assessment and Management Quality Framework. In terms of helping LPAs to judge assessments, there is also a need for an authoritative body such as is found in the fields of flood, ecological, economic, transport and landscape impact assessments. Ultimately, it also needs for some sort of quality assurance system and associated awareness training and guidance for practitioners and users of WLIAs.

Figure 3 Example of Welsh Language Impact Assessment Heat Map

Source: Cwmni Iaith/Burum (2019) Carmarthenshire Draft Deposit LDP Welsh Language Impact Assessment Commissioned by Carmarthenshire County Council

The work I have done with Cwmni Iaith and other practitioners and academics has very much focused on trying to find practical ways on to how to address these issues. We recognise that much work still needs to be done in finding effective solutions and – in the spirit of the Five Ways of Working - we look forward to generating and consolidating discussion and action in trying to ensure Placemaking where a thriving Welsh Language matters.

Owain Wyn, B.Sc.(Econ), M.Sc., MBA, FRTPI

[1] See revisions to Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 (sections 60B(2), 60I(8) and 62(6A))

[2] Welsh Government (2017) Cymraeg 2050 A million Welsh speakers

[3] Office for National Statistics Statistical Bulletin (2020) National population projections: 2018 based As corrected June 2020

[4] Welsh Government (September 2020) Future Wales: the national plan 2040

[5] The Welsh Language Board, HBF, local authorities, et al. (2005) Planning and the Welsh Language – the Way Ahead”